Geography

Table of contents

Introduction

Historical sources will communicate spatial data in a variety of interesting ways that are not always easy to translate into a granular data structure. Spatial references morphed to meet people’s needs and relationships that existed in certain spaces are not always recorded. As such, CHCD has had to implement two unique features regarding how it applies geography to historical sources.

Multi-level Geography Using Modern Administrative Districts

Historical sources might locate individuals or institutions using a street address, a county, or just a province. Capturing these fuzzy geographic references and placing them in some form of space requires varying degrees of geographic specificity. In other words, to place every historical spatial reference on a map, spatial references need to roughly match the exactness of the historical source. Administrative units are the most readily available model for mapping these various levels of geography.

This, of course, causes an immediate problem in a place like China. Which historical administrative break-down should be utilized? If historical place names and administrative units were utilized, it would create several problems:

- Potential Problem 1: It would be more difficult to track spatial relationships over time as the same place might be represented by various nodes in the database

- Potential Problem 2: it would require the time-intensive task of creating a gazetteer of place names and coordinates, a task that would easily take up all the time of the project.

As such, the CHCD has chosen to represent the fuzzy geography of historical sources using point data for the modern administrative map of China (c. 2009). Centroid points are created for each administrative unit and used for locations in the database. Where more granular data is available (e.g. village names and street addresses), researchers locate places individually and place them in the modern geography.

While this runs the risk of reading modern geography into the past (a risk inherent in any historical project), this approach does offer two benefits:

- Benefit 1: Historical subjects from various time frames are placed on the same geographic field, allowing researchers to analyze spatial relationships between them

- Benefit 2: Researchers and students do not have to initially navigate historical administrative divisions to begin understanding the basics of the data.

Controlled Geographic Interaction

Secondly, geography is only created when Institution nodes or Event nodes are related to one of the geographic nodes of the database. This initially seems counter-intuitive as historical persons also inhabited space and moved between spaces. Allowing persons to have geography, however, has two main problems: 1) it increases the chance of redundancy and errors and 2) it is more work. The CHCD solves both of these problems by controlling interaction with geographic nodes.

Reducing the Risk of Redundancy and Errors

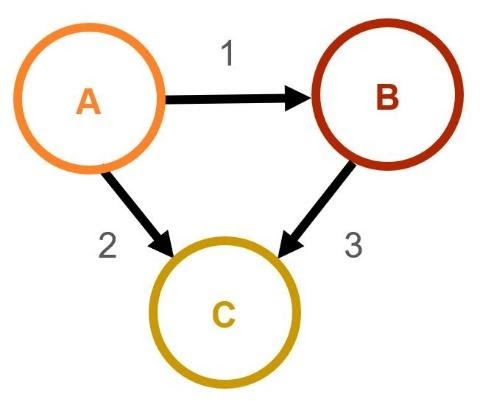

Recording the location of people and institutions separately is a clear form of redundancy. Take the following example; Person A is present at Church B and both are in Village C. If these relationships were recorded separately the graph would look like this.

In this schema, relationships 2 and 3 are communicating essentially the same data. Moreover, if the institution were to change cities, two new relationships would need to be created. Errors are more probable because of this redundant relationship. For example, if a researchers discovered that the institution was actually located in a nearby village, Village D, they would go to the database and change relationship 3. In order to update the relevant individual location they would need to query the database for a list of all personnel who are related to Institution B and Village C, and then they would need to manually update them. Any human slip could cause a massive amount of erroneous data.

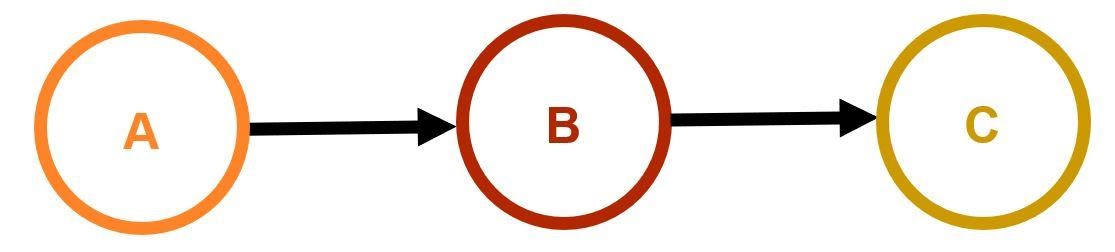

The below CHCD schema eliminates this redundancy, reduces the number of relationships needed to communicate the same information, and minimizes the potential for erroneous data.

Decrease in the Amount of Work

As demonstrated above, giving individuals unique relationships to geography can dramatically increase the amount of work needed to update historical markers. In this instance, controlling the connectivity between nodes allows the data structure to remain easy to update and modify without a massive amount of repeated actions. Consider the above example again. If there were 10 individuals connected to Institution B, a direct person-to-geography model would require creating 21 relationships. If the Village was modified, it would require altering 11 of those relationships. The CHCD model only requires 11 relationships to convey the same amount of information and the same change would only require modifying 1 relationship.

General Areas

The controlled geography system of the database requires the use of general areas, as individuals may be present in a location without being directly linked to an institution. If all that is known about an individual is that they are in an area, the schema requires a default geographically linked general area to place them.

:GeneralArea nodes are named in the following way:

FORMAT

General Area (Location Name)

EXAMPLE

General Area (Beijing)

Note: Without care, researchers can interpret general area data incorrectly if they forgot that individuals are only connected to a general area if they cannot be affiliated with an event or an institution instead. Therefore, general area nodes cannot be used to determine all the individuals present at a given location. Most individuals in the database are linked to events and institutions as opposed to general areas.

Geographic Code System

The multi-level geography CHCD depends upon the modern administrative divisions of China (c. 2009). While the original place name spellings should be recorded, the :Geography are names according to the modern geography of China.

To aid in the collection of data, the CHCD team has created a Geography Code system whereby each of the administrative divisions of China can be referenced through a short alphanumeric ID.

When recording geographic information, please use this spreadsheet to ensure that your data can be accurately placed on the map. Currently, the code system includes codes for all county-level, prefecture-level, and province-level administrative divisions.

Click the button below to view the geography code system spreadsheet:

Tips on Recording Data with the Geography Code System

When using the geography code system, it is important to try to follow these principles:

- Record the Original Place Name: Romanized spellings of Chinese locations varied a great deal. By recording this information in your spreadsheet, this will allow future researchers to find your data and correlate it to their own resources. Furthermore, this practice turns the CHCD into a de facto gazeteer.

- Locate the Modern Equivalent: Modern locations may have changed names and administrative divisions multiple times throughout history. To the best of your ability, try to supply the geography code of the modern administrative division which occupies the same space as your historical location. This may require some research.

- Be Granular: The CHCD uses centroid points for each administrative division to assign it geography. This means, that the smaller the administrative division is the more accurate its geography is. When recording geographic locations, try your best to find the smallest administrative division which corresponds to your historical location. For example, large cities are often far larger today than they were in the past. Though the historical and modern location might share the same name, it may be necessary to designate a specific district which better corresponds to the actual historical location.

- Be Responsible: The CHCD depends upon the quality of data collected by its partners and collaborating researchers. This means that one should be relatively sure when assigning a geographic code to a historical location. When in doubt of a location, it is always acceptable to assign the location to the geography code of a larger administrative division which you are more sure of.

- Be Careful: Today, China generally has five-levels of administration (village-level, township-level, county-level, prefecture-level, province-level). Sometimes, administrative divisions may be at the same level but employ different nomenclature (e.g. Shanxi Province, Beijing Municipality, Macau Special Zone, and Xinjiang Autonomous Region are all “province-level” divisions). Be aware of these differences, and refer to the Geographic Code System to find the most accurate designation.

- Add More, Be a Hero: It is often improbable, if not impossible, to locate the exact location of a historical village or township and relate it to its modern equivalent. That said, the database is capable of recording village and township level data. Please contact the CHCD project team if you have village or township data that you would like to contribute to the database.